Shirkers Interview: Sandi Tan

“I never thought it was that much of a possibility for me there because there were no film classes, there was no film school. You are just watching a lot of movies and making movies in your head. So I was a filmmaker a long time before I became a physical filmmaker.”

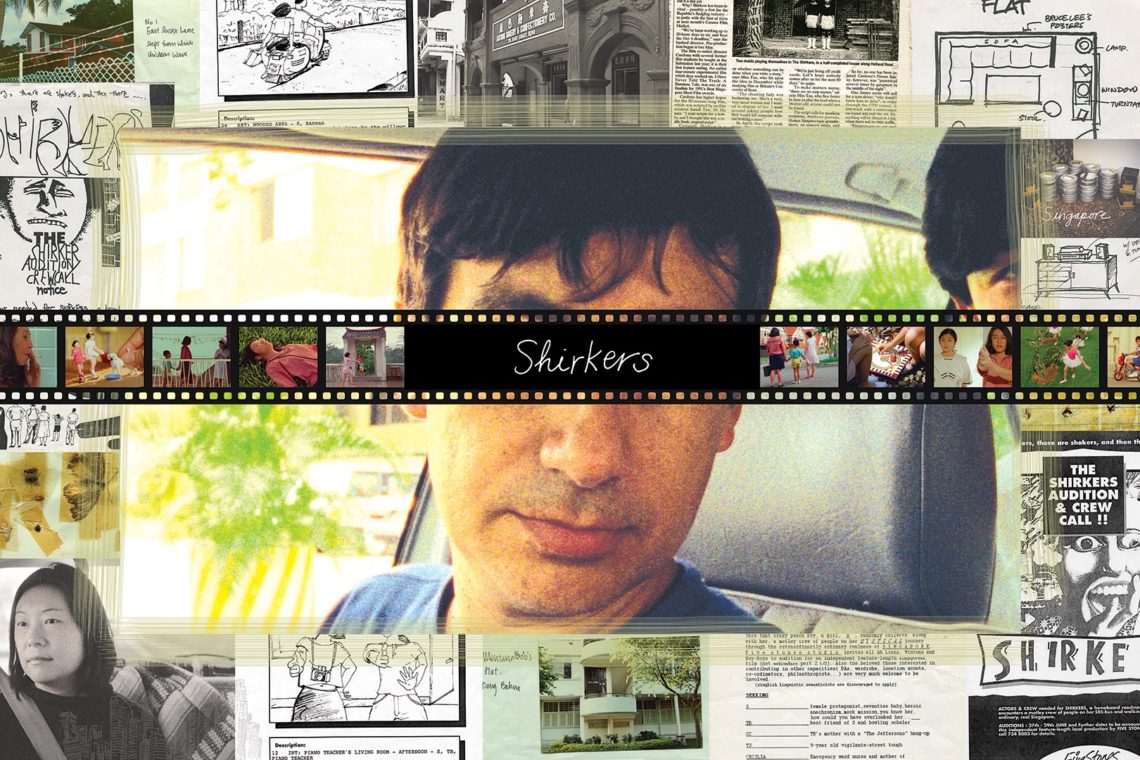

SHIRKERS is a wild ride.

It begins as an amazing tale of three young women making a road movie in a country with no real film industry and very little roads. Inspired by the teacher of Singapore’s first film class, George Cardona, these women create a fascinating movie with donated film, equipment and volunteers.

This is where the documentary really begins.

Cardona, who worked as the director of the first SHIRKERS, disappears with everything. For 25 years, SHIRKERS became a legend. The film that could have been.

Until now.

When footage is recovered, director Sandi Tan goes back to all the people touched by the film, and by the mysterious Cardona, to try and piece together the events that led to the loss of her first project.

I spoke to Tan over the phone about the old SHIRKERS, the mysterious George and the bittersweet tale that became the story for the new SHIRKERS.

I spoke to Tan over the phone about the old SHIRKERS, the mysterious George and the bittersweet tale that became the story for the new SHIRKERS.

You can see SHIRKERS on Netflix on Friday, October 26th.

Can you tell us about yourself and how you got involved in film making?

Sandi Tan: Oh wow, I’ve never gotten that question before. I was always wanting to be a filmmaker since I was a tiny person, I just didn’t know what film making was. I wanted to tell stories. I was always playing with dolls houses and making elaborate, elaborate soap operas and stories with all the characters in my dollhouse. But none of my little cousins I was playing with could ever follow because I had this ongoing narrative in my head all the time.

I was this crazy kid who wanted to do this thing but I had no venue for it. Then I did school plays and all that kind of stuff. I was always into movies, I was into Keanu Reeves and Rob Lowe, those were my gateway drugs to movies. In fact, it was wanting to watch Rivers Edge with Keanu Reeves and being unable to find it in Singapore, led to me hassling the Singapore Film Society into showing the film so I could see it. Because my beloved Keanu and I was never going to be able to see the film in Singapore.

So I got involved in launching some of the things they would show like Fellini’s 8 1/2, Rebel Without a Cause which was also interesting because of those iconic James Dean girls. It was that kind of stuff which got me interested in film making and seeing American films.

I never thought it was that much of a possibility for me there because there were no film classes, there was no film school. You are just watching a lot of movies and making movies in your head. So I was a filmmaker a long time before I became a physical filmmaker.

Then finally when the opportunity came around to make Shirkers I jumped at it. Going to the film class, the first-ever film class that was in Singapore was run by this guy George Cardona and I was 18 when I went to it, that gap between high school and college, and that was the first time I came into contact with making videos and films. That just seemed like ‘oh, this is something I can do.’

Can you tell us about Shirkers the documentary?

ST: I looked at that footage that we found and the vivid images of the primary colours, the amazing faces that we caught in the film and all these locations, I just knew that something had to be done with it. I wanted to make a film that was very much in the spirit of the original, which is very DIY. I handpicked my tribe to make this film, so I did that similarly with this one as a grown-up.

I hand-picked people who seemed unlikely, like my editor, who I worked on the film with for eight or nine months in my garage, he’s a 27-year-old skateboarder named Lucas Celler. He didn’t really have any experience editing a feature film but you really have to pick the least abrasive people, once you find these people, the right people, you just got to be able to trust them and work with them.

I found a sound designer Lawrence Everson in LA who is a really amazing sound designer who could pull all the elements through together with me and help make memory alive for me in the film.

It was a process mainly of finding the right people. It was very much like I was reliving the original Shirkers, in which I played S, this character, this 16-year-old killer who was going around finding the right people to kill and take them along with her into the next world. Which is like finding your tribe and holding them close to you.

In making this new version of Shirkers I would say the same thing, re-finding these people, making this thing where I had to search out all these people who had been involved in Shirkers or somehow whose lives were touched by George and bring them into this grander narrative of the grown-up Shirkers.

Can you talk about that process of going back and finding the people that worked on the film or had contact with George and what that was like for you and for them to re-live this experience.

ST: It was very fraught for all of us because it’s a very radioactive subject for a lot of us, both the film and the loss of the film and George himself. I had the benefit of making the film so I was in control of the story and I was going through a personal journey making it. Being a detective of my own life. Putting the pieces together, putting the pieces of this jigsaw puzzle together.

So I was actively doing that and there were people I can imagine who felt more helpless. I was just seeking them out and persuading them to be part of this thing. There was a lot of reluctance at first and dithering and changing of minds. The widow changed her mind about ten times. But I think all in all it was cathartic for everyone to get involved in this thing that was an unsolved mystery almost. An unfinished business from 25 years ago.

When George vanished with the film we had nothing to say to all these people like the woman who played the nurse, who gave a great performance, everybody who gave up their time for free. These people were all volunteers, all the kids who worked on the film, we had nothing to say to them. They never knew what happened, they had no answers.

But now we have proof and it was going to come back together again. It was a very bittersweet thing, I think, for a lot of people.

In the film, you talk about how there was no real film landscape in Singapore. Do you think if Shirkers had been released it would have helped to move things along?

ST: Some people think that film historians and film programmers and critics think that it would have been a call for ‘let’s do something different. I mean these kids can do it from nothing and make this crazy film on nothing.’ This could have reshaped or established a look or a feel or kind of an anthem for kids or grown-ups to go and do it and be brave and try something different.

Instead what happened was people made social realist films, not my kind of films, and the film scene in Singapore just never had youthful energy or risk-taking.

It’s not for me to say. What I think myself is that if we had finished this film and it was put together, it wasn’t going to be perfect. People are used to seeing Jurassic Park or Titanic or even Rambo, they see all those films and they won’t know what to make of it [Shirkers]. They might not have been so enthusiastic or encouraging and they would have shamed us maybe. We might have been discouraged and we might have had an alternate past in which the three of us are no longer involved in film and we’re doing grown-up, boring jobs in a different direction, or interesting grown-up jobs in a different direction.

Instead, the dream was kept alive for us because the film never got finished. The three of us went on dreaming about being close to film.

This is your first feature film.

ST: In a way.

Did you decide to make this documentary as your first film because it was in a way still Shirkers and you could now explain your actual first film?

ST: I think finding the footage is where this lie was born, this kind of explains the context and the story is so much more interesting than the original Shirkers. This is a fascinating, stranger than fiction story, I think.

George, I think, is a very, very compelling figure. He’s not a villain but he’s a very compelling figure that we often see in American culture. The self-made man. He’s a composite of many different, fictional parts. He reinvented himself in America and I find the whole situation, the whole story as a way of me coming to terms with my life. Getting back with my friends again, a strange kind of reunion, a bittersweet reunion.

How could you not want to make this film?

People are calling George a villain, you said he is not a villain and I agree, he feels so human. Can you speak about this?

ST: I think he was overwhelmed. He was human in that he was stuck in a spot and didn’t know what to do. I don’t think he realized that we would actually pull this off. He didn’t know that we would get free film and labour and that we would actually do this. He was a man who lives in the realm of stories and he probably never thought we would get to this spot where we would actually be filming. Every day going ahead he was fully, fully going insane, he couldn’t keep up with it.

On some level, he didn’t think it would actually happen and I think when he ran off with the stuff he didn’t want to come to terms with finishing something because then he would be judged by it. But he was also overwhelmed. Our inexperience and the fact that it was these young women who were running the show. He was twice our age and supposedly was the man with experience so I think that for him makes him human.

It’s nefarious but it’s also what you need to call him a villain because he’s somebody like many male mentors that women have in today’s world who both enable and thwart your ambitions. This was a very interesting version of that story.

Can you speak about any of the women who worked on either version of Shirkers?

ST: In the first film we had Jas [Jasmine Kin Kia Ng] who was the assistant director and Sophie [Sophia Siddique Harvey] was the producer who was writing all these letters and getting all this equipment for us. There were a lot of us, our production designer, working behind the scenes, makeup artists, property masters, there was a whole bunch of us pulling together, it wasn’t just women.

On this Shirkers it was me, one of my editors Kimberly Hassett, my second editor is great. She would help me tease out the storylines that were more personal that I couldn’t work on with Lucas because he’s a young man who wasn’t comfortable with certain things.

I worked with two producers Jessica Levin, my friend from film school, who also just produced Manic for Netflix and also Godless. Maya Rudolph also helped out on this.

Iris Ng the DP who is from Toronto and shot Stories We Tell and Making a Murderer. She was my main eyes through this film. She shot the interviews with me, and it was crucial that a female DP was a small Asian lady who could vanish into the room. That was very important to me because I had male friends who were DPs who were very upset that I didn’t hire them but I tried to explain trying to be sensitive that it was crucial that I needed a very specific type for this particular project.

You just have to pick the right people very carefully for the right jobs and then trust them.

Who are your favourite women working in the industry that influenced you?

ST: Jane Campion when I was a teenager when she made Angel At My Table. That was a movie I really loved, that was a movie that showed me it was possible to tell a story in a longer than 90-minute form about an interesting, normal female heroine. There are so many but I think Jane Campion is consistently interesting.

It’s hard for me to think about this, I don’t usually think about male and female directors, maybe I should.

I think Jenji Kohan is doing interesting work on TV so is [the team behind] Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Jill Soloway is doing really interesting work as well. Female writers seem to find a lot of space on TV for their voices.

What are you working on now or next?

ST: I’m working on promoting the film. I’m talking to a bunch of people about a bunch of different things that I can’t talk about right now but am very, very excited about.

*This post was originally featured on The MUFF Society.*